RIPOFF

LENA CHRISTAKIS

RONAN DAY-LEWIS

September 7 - 12 , 2022

625 Madison Avenue, New York City Room #1023

|

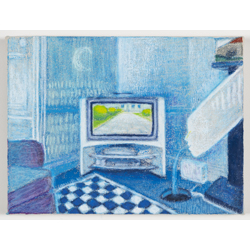

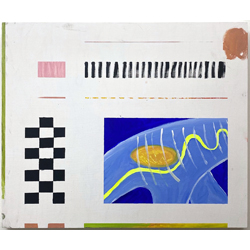

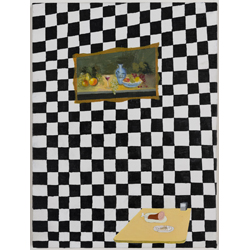

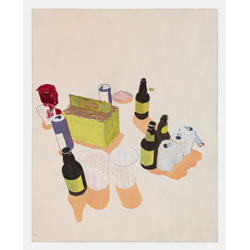

Artist couple Lena Christakis and Ronan Day-Lewis met as undergraduates in the art program at Yale and have been together since. Their presentation at Spring/Break will make public a version of their shared Ridgewood studio.Sharing the daily conversation of making work in the same room, the two artists found they were influencing eachother in ways that were beyond their control, sometimes even stealing from and copying one another. In Ripoff, these bodies of work are put in contrast and concert with one another, illuminating similarities and stark contrasts.The space is installed with physical versions of elements the practices share, as if allowing us to enter the commonimaginary worlds of the work. Choosing to show their work together as a couple, Christakis and Day-Lewis present a counterpoint to the myth of the artist as individual genius or island, or lone parasite as Burroughs might have it. Positioning their works in conversation with one another, they interrogate originality as a primary virtue, in which the artist’s ideas, style or other trademark must be protected. Instead, they offer a glimpse into processes of osmosis and cross pollination between artists, and by extension how we help each other grow, not directly but in tiny and mysterious ways. Being in a tradition of painting means learning by imitation of masters, but often history overlooks how art grows within the safety of intimate human friendships. Christakis’s work elaborates on the highly coded still life genre, expanding the memento mori to more ambiguous ends. Sparsely-arranged objects in un(der)defined environments––somewhere between a looming abyss and a celestial promise of possibility––speak simultaneously to multiple realities of the human condition. Loneliness, vanitas, uncertainty; alongside hope, humor, pleasure. In To Eat and Drink Sumptuously, a “traditional” still life painting modeled after a cheesy printed canvas in a local pizza joint hangs behind a table scene of a cartoonish ham and fish bone, with a napkin dispenser New Yorkers might recognize from soaking up the extra grease on their no-longer-$1 slices. Food as both sustenance and over-indulgence permeates the painting, which recalls at once the weight of art history and a cartoon cat’s hunger-induced hallucinations. In Copy and Paste, Christakis confronts her viewer with hedonism in the extreme. Here, “overfull” is a visual argument and an imagined physical state, as slices of cake, glasses of wine, oysters, and steaks multiply (and continuously so, as partially realized, seemingly ever-emerging treats would suggest). The title nods to Christakis’s use of emojis, which serve as the model for many of her painted objects. While the cookie-cutter cake slice taken from Apple’s emoji dictionary adds a certain familiarity to the work, Christakis is more interested in the distance between her paintings and the real objects they supposedly represent. A cake emoji designed as a stand-in symbol for all cakes, or even all things sweet, becomes a vehicle of communication––literal or figurative, genuine or ironic. Juxtaposing different modes of representation, from the hyper-flat to the hyper-real, Christakis relishes in the space this distance creates. Day-Lewis’ paintings push the conventions of landscape and figuration into strange and bloody waters. Redolent of Romanticism in their search for the emotive and sublime in landscape – and Fauvism in their striking sense of color– the hallucinatory pastoral scenes in Day-Lewis’s paintings are less observations of outside places than impressions of internal ones; emotional topographies brimming with the beauty and horror of existence. A longing for transcendence pervades the work, but the object of yearning is always something just beyond reach; arched windows, distant doorways, television screens, and holes in the ground offer glimpses of tantalizing secret worlds. To Day-Lewis, the sublime is defined by its inaccessibility. His strange landscapes are inhabited by mythical beings whose melancholic, almost human faces jut from quadrupedal bodies. In Half Light (Can’t Believe How Strange It Is To Be Anything At All), the largest work by Day-Lewis in the exhibition, three of these mysterious creatures stand on a vast checkered picnic blanket receding towards a sky fizzing with electricity. Lightning flashes in the distance, throwing everything into an uncanny luminosity. The cryptids’ checkered carapaces appear to be caught in the midst of a process – half-way between biological and digital – of disintegration, or maybe integration. Windows into their insides reveal blood coursing through serpentine entrails beneath white hot ribs. Bones protrude from the ground, collapsing the materials of life and death. Objects scatter the psychotropic contours of the landscape, some of them shared with or stolen from Christakis’ iconography: a pool ball inscribed with the number 11; a half-decomposed fish; an old TV; a burning circus tent; a circular hole filled with some viscous plasma. Put in unlikely configuration, |